Danny Kaye and the Ying's Thing

The accidental Hollywood phenom/diplomat/heart surgeon/orchestra conductor/jet pilot/baseball titan/cook who became one of the most widely-celebrated Chinese chefs of his era.

To those who are of, or appreciate, entertainment of a certain vintage, you already know that Danny Kaye was master of many trades; but being one of the most celebrated Chinese chefs in America is probably the lesser-known and most surprising among them.

If this sounds like the conceit of a Hollywood celebrity exaggerating their kitchen prowess while appropriating a nation's cuisine, you're very much not alone. Almost every profile by a noted food critic, chef, or culinary historian of the time rides in on the premise that people were paying lip service to Kaye's abilities, only to admit (begrudgingly, sometimes) that it was one of the finest meals of their lives.

Aggressively trained in his spare time under the skilled watch of luminary chefs Johnny Kan and Cecilia Chiang, Kaye went on to work in renowned Chinese kitchens between filming, where he would serve seemingly endless banquets to 200+ studio executives at a time, train pupils in the art of authentic Chinese cooking, and later open an improbable 8-seat restaurant (which he dubbed "Ying's Thing") in the alleyway behind his home. These pursuits concluded with him earning an honorary Les Meilleurs Ouvriers de France, the only American cook in history to claim such an award.

Covering a fraction of the life of an extremely complicated entertainer who taught himself open-heart surgery, was a well-decorated pilot, conducted world-class orchestras without reading a note of music, and who Jacques Pepin once said "operated the best restaurant in California" can easily digress into a novel. Still, I've tried to hinge most of this on his discovery and profound love of cooking.

Danny Kaye's life began as David Kaminsky of Brooklyn on January 18, 1911. The youngest son of working-class Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants from Dnipropetrovsk, he was the only American-born member of the family. Kaye seemed to have a childhood full of happiness and encouragement - he spoke Russian and Yiddish at home in Bushwick and considered himself blessed to grow up in working-class Brooklyn - in his words, "Everyone born here liked a person for who he was, not for where he came from or who his parents were."

His mother passed away when Kaye was 13, prompting a temporary runaway to Florida, where he busked and performed under the name "The Harmony Kings" with his best friend, Lou Eisen. While it could be presumed that he did this due to the trauma of his mother's death, Kaye insisted that he was just "bursting with curiosity about the world outside Brooklyn" . Although this dalliance ended as quickly as it began, he and Eisen would continue to spend their summers performing at White Roe Lake Hotel (a jewel of the Catskills borscht belt) where he also found work as tummler, honing the improvisational, dance, and comedic talents that would lead him down the path to Broadway.

At home, his father (whom Kaye described as "a simple tailor, and pleased to be one") guided him with a gentle hand, granting him his space to develop his own ambitions without pressuring him to return to school or select a trade. His father was also credited with shaping Danny's first impressions of cooking, telling Craig Claiborne of the borscht, schav's, and Russian comfort foods his father would prepare for his family, noting, "He got so much joy out of raw ingredients, and I think I inherited that."

Outside the summer's on the stage, Danny spent the remainder of his youth working, and being fired from, various jobs that ranged from delivery boy to dental assistant, the latter of which he was sacked for using the dental drill on the office woodwork out of sheer boredom. His apology came later, in the form of out-of-state elopement to the Dentist's daughter; more on that later!

Kaye's first big break came when he was invited to join the vaudeville dance group The Three Terpsichoreans in NYC. Shortly after he signed on, they received an invitation to perform in Asia in a series of USO shows. Danny's comedic timing, slapstick body language, expressive delivery, and madcap facial expressions were on full display, and it became apparent to everyone that this was a man who could connect just as easily to a foreign audience as an American one.

The Three Terpsichoreans. Retrieved from the Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186327/.

In 1934 he traveled to Shanghai with the group, which led to his first exposure to Chinese kitchens. While his fellow performers and crew spent their days bargain-hunting in the markets, Kaye spent his navigating the restaurants whose food felt to him like a quasi-spiritual awakening. He got to enter the kitchen after one such meal and stated, "it was overwhelming; 180 degrees in contrast to anything I'd ever experienced in the Western world. I was absolutely riveted by the heat, the flames, and the technical speed of the chefs." While this didn't seem to motivate Danny to immediately pursue cooking himself, it was certainly left to ferment and defined the caliber of food he sought out in the years of his celebrity ascent.

Back in the US, Kaye appeared in two-reel comedies and continued his work in the Catskills. In 1939 he took an audition for Broadway's Straw Hat Review and connected with a quiet but strong-willed pianist (and aforementioned Dentist's daughter) named Sylvia Fine, whom he had met in Brooklyn as a boy. They eloped in Florida in 1940 after a brief courtship and formed a symbiotic professional partnership that would last a lifetime. Fine served as his manager, and Kaye leaned heavily on her exacting and prodigious creativity in all of his works - she wrote almost all of his stage and film material and even served behind the scenes as an editor and producer, always writing based on what she was certain Danny could execute.

At 30, Kaye got his first major dose of exposure for his performance in Broadway's "Lady In The Dark," where he performed "Tschaikowsky (and Other Russians)" as written by Kurt Weil and Ira Gershwin. His ensuing Manhattan supper club shows and his appearance in Cole Porter's Broadway hit "Let's Face It" garnered a lot of "first big New York star in 20 years" -type press coverage, which is when Samuel Goldwyn came knocking at his door.

Louis Armstrong and Danny Kaye reviving The Saint Go Marching In (from their duet in The Five Pennies) on the Danny Kaye Show. The patter lyrics were written by Sylvia Fine.

This is the exact moment where Danny Kaye was "made" and I won't wade too deeply into these waters. Goldwyn (in an abhorrent but predictable 1930's move) worked with his team to remake Kaye's appearance, eventually dying his hair blonde to offset his Ashkenazi features. Kaye recalled Sam's assessment, in his usual self-deprecating fashion, as "We have to be very careful how we handle this boy because he's not good looking, he can't act, and he has no sex appeal."

His big debut would be 1944's "Up In Arms" opposite Dinah Shore, where he played a hypochondriac soldier - not much of a stretch considering Kaye was an unapologetic hypochondriac himself. This marked Danny's well-documented rise through the 1960's - he would star in 19 films and produce 7 albums, write several books, host the Academy Awards, woo royalty with a stint at London's Palladium, snatch a role created for Fred Astaire (White Christmas - a testament to his hard-won dancing talents), entertain troops in Korea, Vietnam, and WWII, and go on to collect Oscar's, Emmy's, Peabody's, Golden Globes, every Israeli accolade, the French Legion and a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

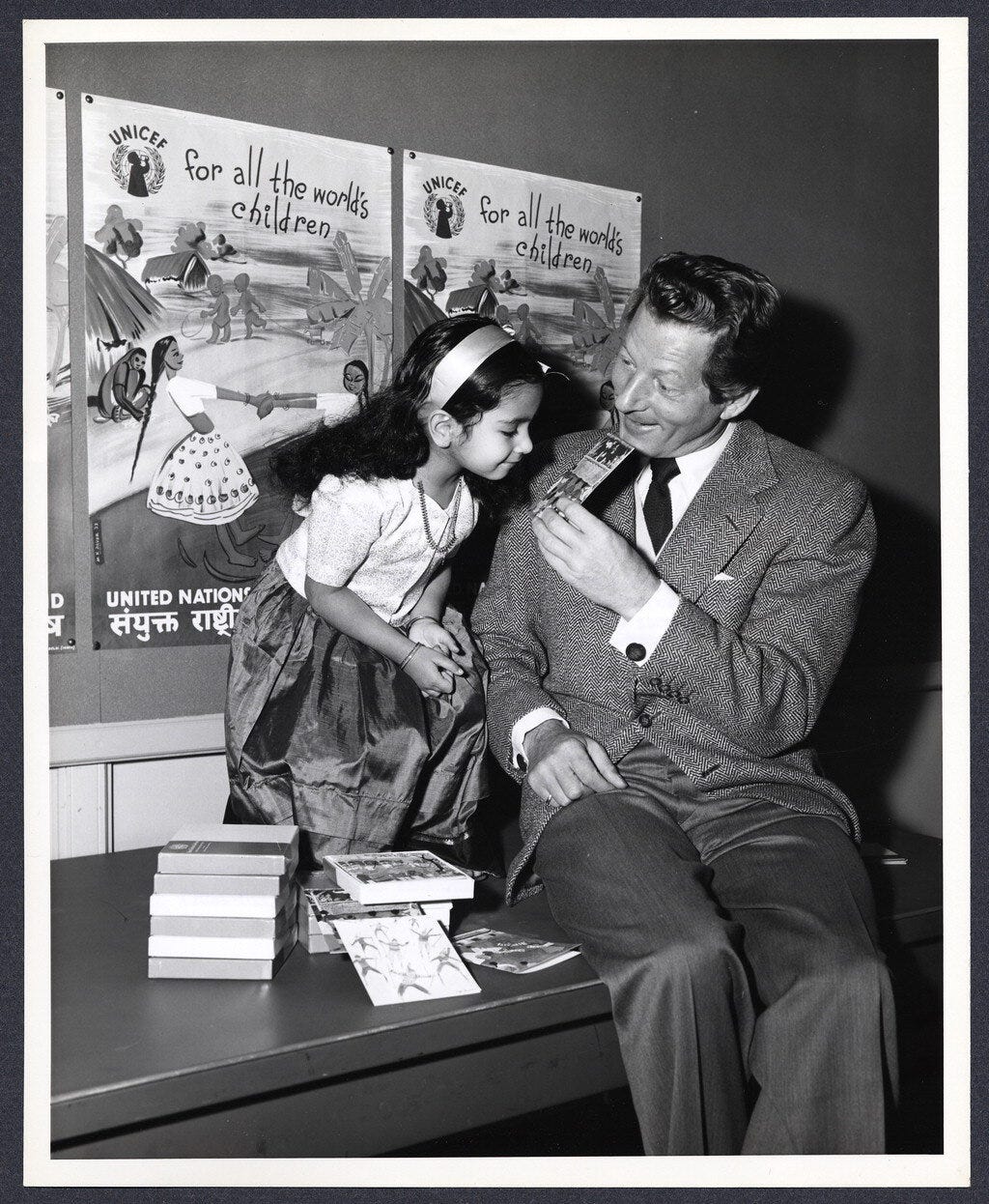

Starting in 1954, he was appointed the first UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador to Children, which ended up being one of the great joys of his life. Danny had one daughter, Dena, and truly loved kids, which is evident through all the wonderful children's records he and Sylvia produced over the years. Footage captured on his missions shows how easily kids flocked to him (again, his schtick and childlike naivete immediately translated to foreign audiences), and he happily did outreach with the organization until his death, a lovely counter-narrative to some of his well-chronicled darker traits.

Danny Kaye during work with UNICEF. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186596/.

The portrait painted of Kaye after he reached A-list status demonstrates a man full of rough-hewn contradictions. His biographer, Martin Gottfried, rightfully described him as "elfin and warm" onstage, but he continued to become more withdrawn and broody over his lifetime. Tony Curtis famously labeled him a bully. He could become sour at the drop of a hat, grow irate with adult fans, and was a notoriously impatient man who needed to constantly be the center of attention and despised small talk. His daughter Dena gave a colorful affordance for the latter in a tribute article: "He hated small talk for the same reason he hated five-minute interviews: he felt nothing could be discussed meaningfully. In one case, he went to a [cocktail] reception, relieved the waitress of a large tray of hors d'oeurves, made his way around the room serving astonished guests until the tray was empty, and left."

Conversely, people have described him as generous, tenacious, an attentive listener, a man who had very high standards for people but was never snobbish or pulled rank, and who was a curious perfectionist in everything he pursued. Reading between the lines, he was that tired "prodigal male chef" trope, only forged in a different fire with a unique set of privileges (and an annoying preternatural ability to excel in anything he touched).

The obsession with Chinese cooking was preceded by a ton of other obsessions, memorized and perfected at a breakneck pace. He was a lifelong Dodgers devotee, recording a hit anthem for the team, and became a talented second-baseman and part-owner of the Seattle Mariners. A quasi-businessman, he owned a chain of radio stations under Kaye-Smith enterprises, which also served as a concert promotion company, a video production company, and a high-end recording studio. He developed an interest in flying, obtaining a license for multi-engine aircraft before he even received a license for a single-engine plane. Kaye obtained a commercial pilot's license and was anointed vice-president of Learjet by its president (a title in honor only), later flying one of their jets to 65 cities in five days to visit children on the tarmac for UNICEF's Halloween drive in 1985. This cemented Kaye's place in the Guinness Book of World Records for most piloted stops in one stretch.

He longed to be a surgeon in his youth (but knew the education was out of reach for his family) and amassed so much knowledge about open-heart surgery and other fine-tuned medical procedures that he was made an honorary member of the American College of Surgeons and the American Academy of Pediatrics. He took a fencing class for a scene in "The Court Jester" and became so adept with a sword that the fencing instructor had to stand in for the opponent actor for liability purposes. In the '60s and '70s, Kaye regularly conducted The New York Philharmonic and other world-renowned orchestras, learning all the scores by ear. Dimitri Mitropoulos (conductor of the NY Philharmonic) noted, "Here is a man who is not musically trained, who cannot even read music, and he gets more out of my orchestra than I have." Kaye never accepted a fee for his appearances as a conductor, raising $6 million primarily for the orchestral musician's pension fund.

Amidst this exhausting Walter Mitty-ish list of hobbies and interests, Kaye began the next leg of his career in 1963 with his Emmy-winning weekly variety show. It seems like Danny envisioned a different cadence for the second half of his career, bolstering the reputations of other artists and dedicating himself more to alternate projects after the whirlwind pace of his film career through the 1950s. This is also the time he started dedicating himself to the kitchen in earnest.

Baby Dena Kaye and Danny Kaye. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186397/.

Dena Kaye was a teenager at this time and shared her memories of the early 1960s (full of amusing tales of A-listers circulating through their home) for a piece on the Kaye-Fine estate in Architectural Digest, as well as a few other retrospectives offered up for Danny's centennial. It all starts innocently enough as she recalls a man who preferred to entertain at home and "loved good caviar and Kentucky Fried Chicken equally" and "would "flake out" on the couch for days at a time, watching talk shows, Julia Child and the Dodgers, eating black licorice and BLT's." He started to find his way into the kitchen, cooking modest Italian dishes like linguine al vongole, which served as the gateway to making his own pasta, which (of course) escalated to his bona fide status as an Italian chef, specializing in many peasant dishes that had fallen out of favor in the era that oscillated between high-end French cuisine and convenience foods. From this point onward, if Danny was home, he could be found in the kitchen.

Sometime around the first broadcast of 'The Danny Kaye Show,'’ its namesake started spending an awful alot of time in San Francisco, specifically inside Johnny Kan's eponymous restaurant at 708 Grant Street. Kan, who was raised in the suburbs of Portland at the turn of the century and whose family's home cooking was the stuff of legend (according to letters from his boyhood friend and neighbor, James Beard), had become a culinary darling in the past decade after the release of Eight Immortal Flavors engaged the food establishment and gourmand set in authentic Cantonese cooking with its release in 1953.

Kaye often flew his jet to indulge in a quick meal and Kan's warm company, which wasn't unique at a time when the restaurant frequently hosted the likes of the Rat Pack and Marilyn Monroe - but as with most stories about Kaye, things escalated quickly as he started making his way back-of-house. As Kaye said to Craig Claiborne, "Johnny and I became friends, and for weeks he let me stand around his kitchen and watch. Eventually, they let me do a little chopping and a few of the simpler dishes."

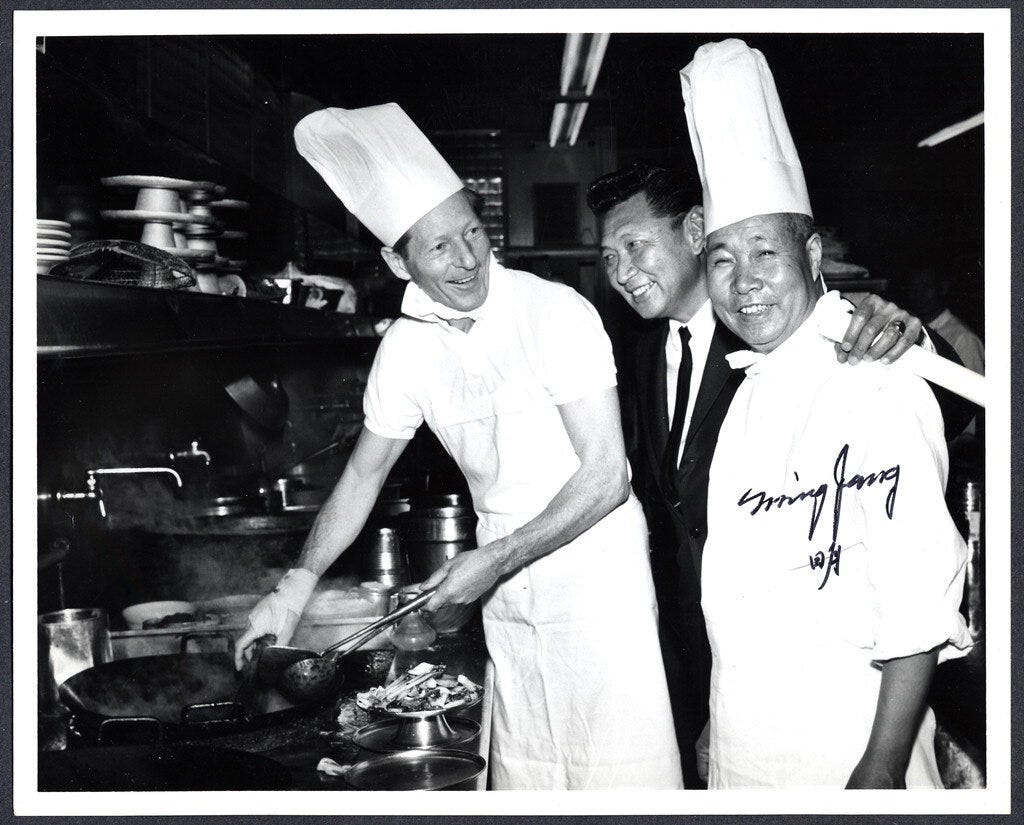

Danny Kaye with Chinese chef Ming Jang and Johnny Kan. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197220/.

As Kaye's skills grew and he gained more respect from the kitchen staff, it seems evident (from the slew of existing photographs) that he became a semi-regular fixture in the kitchen during service hours, despite what must have been an absolutely chockablock schedule. Famously, Walter Cronkite was once dining at Kan's when he was in town covering the 1964 Republican convention - Kan sheepishly asked if he would like to pay homage to the chef who prepared his meal and squired Cronkite into the kitchen, where he came face-to-face with chef Danny Kaye replete with chef's toque.

In 1967 Kaye made headlines when he tackled head chef duties at Kan's for a CBS press banquet of 200 astonished TV executives, and his participation in the kitchen seems to have been consistent throughout the rest of the 1960s and early 1970s, working alongside head chef Pin Wong as his schedule allowed. In 1972 Kaye visited Johnny in the hospital a week or two before his death from cancer, which must have been a tremendous loss for him. Despite the necessary sparseness of Kaye's home kitchen, his single wall adornment was a simple piece of Chinese calligraphy reading "Danny Kaye, skilled hands" a gift from one of the chefs after mastering the line in Kan's kitchen.

During his occupation of Kan's kitchen, Kaye also grew enamored with Cecilia Chiang's Mandarin Restaurant in San Francisco (I believe the original location, shortly before she was anointed "best Chinese restaurant in America" and relocated to the 300-seat location in Ghiradelli square) and studied Mandarin cooking techniques under her exquisite eye. As you can view for yourself in the sweet testament above, Cecilia also thought he was an emerging talent and seemed to love butting heads with him in her kitchen.

Cecilia Chiang on cooking with Danny Kaye (CBS Sunday Morning - Nov 23, 2014)

After years of hosting celebrity diners at the San Francisco location, Kaye was apparently the one who convinced Chiang to open a second Mandarin location in Hollywood. Starting in 1974, she and Kaye co-hosted a cooking class at the LA location, charging attendees (ranging from gourmand homemakers to professional chefs) $20 to prepare an 8-course meal in-house. The Lewiston Evening Journal reported, "Nearly every Tuesday, he's at the Mandarin restaurant here teaching a course on "the ancient and fine art of Chinese cooking" with Cecilia Chiang. [....] Chef Kaye - minus a white hat and apron - began one lesson on Crispy Duck Szechuan Style by picking up a freshly killed fowl and saying, "First, you drop the duck in boiling water to open up the pores. But just give it a half-bath - but no soap! no soap!" Endearingly, Kaye served as a waiter for the students when it was time to eat the meal they had prepared.

Somewhere in this insane mix of moonlighting, Kaye was also building out what would become "Ying's Thing." A separate, shed-like structure built out in the alleyway of his Beverly Hills home, the Chinese kitchen was in addition to the homey one he'd spent so much time in as he was cutting his teeth on Italian cooking in the early 1960s. The table in the kitchen sat 8 (his preferred number of guests). The installations were incredibly ornate for a kitchen inside a residence, featuring multiple burners with concentric rings that conducted such extreme heat that he installed a steel trough in front of the stove that continuously circulated ice water. As such, more BTUs had to be requested from the city of Los Angeles in order to service the space. Claiborne simply summarized, "He has what is undoubtedly the finest Chinese kitchen of any private home in America, and as far as we know, the world."

His daughter, Dena, described the kitchen in Architectural Digest as his stage within the home, and that "no matter what he cooked - his delectable rack of lamb, key lime pie, feathery fettuccine made on his pasta machine, or omelets for lunch - we ate in the Chinese kitchen. My mother called the "real" dining room a "vestigial remnant circa B.C., "Before Chinese."

The Chinese Kitchen a.k.a Ying’s Thing. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200186397/.

Free from the creative obedience required in the high-end kitchens, Kaye began to construct his lavish nine-course dinners for eight guests at a time. Although he had an assistant to help him with prep during the day, he would mostly take on the 24-48 hours of preparations solo, including shopping and maintaining the guest list and menu books to avoid serving repeat meals. Ying's held a casual dress code ("even the king of Sweden had to take off his tie," quipped Dena), but the rules were to eat immediately as each course was placed on the table (apparently bellowing "Don't look at it! Eat it!" like a drill sergeant), and that if you arrived late, God help you. Famously, one diner arrived late to a note taped to the door of the kitchen reading, "You're late. Fuck you." Dena and his former assistant more humanely recalled Kaye's peevish philosophy in a centennial tribute "If you were late, you might never be invited again. He respected other people's time and felt that other's lateness showed a lack for his time. "People said he was difficult, "says Suzanne Hertfelder, his longtime personal assistant. "What is difficult about expecting 100% if you give 100%?"

Guests for dinner included Cary Grant, Audrey Hepburn, Henry Kissinger, Luciano Pavarotti, the soprano Beverly Sills, and the chef’s Paul Bocuse, Roger Vergé of Hostellerie du Moulin de Mougins, Jean Troisgros Frères of Roanne. Danny, always the proletariat, also included friendly bank tellers, accountants, taxi drivers who showed enthusiasm for food and cooking, mixing them among the well-heeled guests. His planning and execution never seemed to deviate based on who was coming for dinner; a friend once asked him if he was nervous cooking for France's most eminent chefs in one sitting, and Kaye responded sharply, "why should I be nervous? What do they know about Chinese cooking?"

A memorial by William Rice in the Chicago Tribune illustrated what it was like to lay claim to a seat at Ying's, stating, "Once there, you were a prisoner of the chef. He decided when you ate and what and where you sat and commanded silence whenever a dish was served. Only rarely did he sit with his guests. Instead, he would kibitz for a time, then move to the stove and in a frenzy of activity produce a celestial hot and sour soup or fegato Veneziana."

Reviews of Kaye's meals and kitchen finesse never wavered from commendation, with guests gaining as much enjoyment from watching Danny balletically prepare the food as they did eating it. Olive Behrent (former president of the LA Philharmonic) noted, "The trouble with Danny's cooking, [is it] spoils you forever for going to restaurants. You could eat in his home every night for a month and never be served the same dish twice." The honorary Meilleurs Ouvriers de France was seemingly drafted before Bocuse had tucked into his dessert. But Ruth Reichl, who was close to Kaye towards the end of his life, probably gave the most vivid and loving account of what it was like to be at the mercy of the chef inside Ying's in her memorial piece for the LA Times:

"Danny Kaye didn't cook like a star. He didn't coddle you with caviar or smother you in truffles. He had no interest in complicated concoctions or exotic ingredients. His taste was absolutely true, and he was the least pretentious cook I've ever encountered. The meals he made were little symphonies - balanced, perfectly timed, totally rounded."

Danny Kaye serves guests in his Chinese kitchen. Dena Kaye seated in the middle. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197219/.

Many reflections on Kaye's cooking echo these sentiments - regardless of all the skills honed in famous kitchens, Danny seemed to possess a sublime taste memory and sense of timing. When you think about the praise he earned for his other talents - his "near-perfect" pitch, his universal comedic timing, his ability to memorize textbooks and conduct orchestras after simply listening to the scores by ear, you realize his collective skills were a mix of stubborn dedication, superb recall, and having an almost celestial handle on his five senses.

While the food he produced and the company he would serve wasn't rooted in classism, Kaye was still a celebrity and certainly had no problem (nay, required) praise for his work and was never beyond bragging about whom he fed, which chefs adored his food, the superiority of his kitchen and custom gear, how his walls were lined with rarefied cookbooks, and the perfect produce he gathered. But when I watch Kaye's 1979 appearance co-hosting The Muppet Show alongside The Swedish Chef, I can't help but think that this was the highest culinary honor you could grant someone who was as childlike as they were earnest when actually cooking.

Danny Kaye on The Muppet Show (1979)

A few months ago, Danny called on the spur of the moment. He was cooking and wanted me to come for dinner. "I'd love to," I said, "but I've got other plans." "Cancel them," he insisted. I told him not to behave like a star. "Ok, babe," he said finally. "There will be other dinners." I wish I'd gone." - Ruth Reichl (LA Times, March 1987)

Danny Kaye had undergone quadruple-bypass heart surgery in 1983, which ended with him contracting hepatitis C from a blood transfusion. After his recovery from surgery, he had a few comparatively low-key years of guest television appearances, cooking stints, and charitable missions with UNICEF before he died of heart failure on March 3, 1987, at the age of 76. His ashes were buried in Valhalla, New York, beneath a bench that contains friezes of a baseball and bat, an aircraft, a piano, a flower pot, musical notes, and a chef's toque.

Almost echoing that frieze, writer and director Melville Shavelson mused, "Sometimes he was my friend, sometimes he was my Chinese chef, sometimes he was my pilot. But I don't feel that I ever really knew who Danny was. He was so many different people, I don't think Danny knew who he was himself."

In October of 1993, the Culinary Institute of America (to whom Fine had donated his 500 cookbooks) dedicated The Danny Kaye Theatre at their Hyde Park campus to acknowledge his contributions to America's culinary landscape. At the time of the dedication, Swiss chef Anton Mosimann reflected on the life of the man he had adored cooking alongside, plainly stating, "I think if Danny Kaye would have become a cook, or a chef, in his early days, he would have been one of the greatest, ever."

But I'd prefer to end this not waxing on the chef that could have been, but the sincerity of the one he was. During those cooking classes Danny taught with so much gusto alongside Chiang in Hollywood, he had only one suggestion for the students after they finished their meal and wandered off into the goodnight:

"Cooking is an expression of one's being that minute. And if you're not cooking with joy and love and happiness, you're not cooking well."

NTR: I wrote this piece for an ill-fated blog last year. More pieces to come, hopefully with a diminshed word count. Thanks for going on a long walk with me!