The Marvelous Life of Esther Eng

A look at the Cantonese-American producer, director, queer icon, and serial restauranteur who became a darling of the New York dining scene by the 1950s.

Here’s the story of a mesmerizing woman, known as Brother Ha to her friends, who produced the first Cantonese talkie in Hollywood, directed 10 films, and went on to run five successful NYC restaurants. She was caretaker to legions of defecting entertainers from the PRC, lived her entire life openly gay, played 13-card poker games at $10,000 a hand, and rocked a “boyish bob” like no one in the last century. But, most notably, she was the hand that gently guided New Yorkers away from the Chop Suey houses of yesteryear and into a more glamorous world of Chinese dining.

Esther Eng was born Ng Kam-ha in San Francisco in 1914, one of ten children whose grandparents had immigrated from the Guangdong area in the late 19th century. Her father, a successful second-generation Chinatown businessman, insisted that all his children go to Chinese-centric schools and speak Cantonese at home. Her entire family, but especially her father, instilled in Esther a deep love of cooking and Cantonese opera - but, she seemed to focus her energies on being the cinephile of her family, having consumed thousands of films in the local theatres by the time she was a teenager.

That stated, most of her youth was spent in movie theatres and at the opera in San Francisco's Chinatown, where she had the opportunity to mingle with some of China's most prominent visiting players. She took a job at the box office of the Mandarin Theatre as soon as she was eligible to work, further ingratiating herself into the heart of the Chinese acting community- and, incidentally, into the heart of actress Wei Kim Fong, the star of many of her early films.

As Esther was exiting her teenage years, Pearl S. Buck's novel The Good Earth was released, giving Chinese Americans a notable culture bump while eliciting white Americans' sympathies for the Chinese preceding WWII. Esther had auditioned for the film adaptation of the book (for the role of a prostitute, one of the only parts made available to Chinese-American actors in the film - the final casting featured unambiguously European actors). Around the same time, her father, noting the growth of Chinese cultural capital and bolstered patriotism, founded a film production and import company with some local partners, including actor Bruce Wong. Citing Esther’s obvious passion and grit, he anointed her co-producer on their initial ventures when she was just 19.

This undertaking led to a relatively short but dizzying career producing and directing global films driven almost entirely by female protagonists. The first film she made under Cathay Pictures Ltd, Heartache (Sum Hun, released 1936), was shot in eight days on nine reels in Hollywood after Esther and Bruce Wong went on a novice mission to Hollywood to raise capital and research Chinese-Americans' current tastes in film. Heartache, starring the aforementioned Wei Kim Fong, ended up being the first Cantonese-language talking film ever produced in Hollywood.

When Heartache received its Chinese premiere, Esther traveled to Hong Kong alongside Wei Kim Fong and started working on her directorial debut with the nation's largest production company. Coinciding with the start of the second Sino-Japanese war, "National Heroine" (released March 1937) featured Fong in the starring role as a woman fighter pilot whose skill and bravery were equal to any man. The film was granted the "Certificate of Merit" from the Kwangtung Federation of Women's Rights and hailed in the Chinese press as "honoring Chinese womanhood" The success of the film prompted Esther to put down roots in Hong Kong despite the escalating conflicts.

Films that followed included "A Night of Romance, A Lifetime of Regret," “100,000 Lovers", "36 Amazons/It’s a Woman's World," and....well, from the titles, we can infer that twenty-something Esther had found her niche. Between the pressures wrought by the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and the invasive presence of the press as two relationships with her "bosom friends” (the media’s shorthand - although they were generally supportive of her love life) disintegrated in the public eye, Esther opted to move back to San Francisco in 1939 at her father’s behest.

Poster for “A Night of Romance, A Lifetime of Regret” (1938)

Back in America, Esther had a mind to focus on Chinese film distribution through her father's company but soon found herself back in the director's chair. Her most notable work, Golden Gate Girl, was released in 1941 and garnered the most mainstream American acclaim - which, unfortunately for Esther, went exclusively to her male co-director Moon Kwan in the press upon its release. The primary message embedded in the film - timed around the Bowl of Rice Movement in support of Chinese soldiers - was for the Chinese community to unite and work together. The film was also notable for starring Tso Yi-man (dubbed the “Mary Pickford of China”) and for being the first film to feature Bruce Lee, who, through pure happenstance, played the role of an infant girl.

Shortly after Japan’s surrender, Esther’s father passed away. She suddenly found herself in charge of his film import and distribution company, which was heavily engaged in the US, China, Cuba, and Peru. Balancing her duties, she continued to work on films after being invited to direct “Lady From The Blue Lagoon,” featuring opera singer Fe Fe Lee. Together they would form the same artist-muse relationship that Esther had forged with Wei Kim Fong a decade earlier, and Fe Fe’s striking presence would run parallel to Esther’s for the rest of her life.

By age 35, Esther had already directed nine films and was ready to retire from cinema. After completing “Mad Fire, Mad Love” with Fe Fe and actor Ronald Liu in Hawaii, she relocated to New York in 1948 for a fresh start.

To summarize Esther’s impact on film before covering her next act, Kate Taylor-Jones summarizes things neatly in her book "Dekalog 4: On East Asian Filmmakers":

"With ten films to her directors' credit, Esther Eng was a pioneer in many senses. She was the first woman to bring a feminist consciousness regarding equal rights for women and the concerns of American-Chinese lives into her films. As early as the 1930s, she attempted to represent cross-cultural and transnational themes in cinema. She was the first to make Chinese-language films in the US and the first Chinese woman to make sound films in Hollywood (see Law & Bran, 2003). And yet, her work and nearly all other early female directors are notably missing from the film history canon. Todd MacCarthy, a former critic at Variety, wrote about his complete astonishment when he discovered Esther Eng's Golden Gate Girl while reading through Variety's back issues, calling her "one filmmaker [who] has utterly alluded the radar of even the most diligent feminist historians and sinophiles."

The trailer for the brilliant documentary Golden Gate Girls by S. Louisa Wei, the absolute authority on all things Esther Eng. You can rent the film on Vimeo.

As Esther was settling into her new life in New York and sketching out plans for a restaurant venture, a group of Cantonese opera players found themselves stranded in Canada as the civil war broke out in China. Knowing what awaited them back home, they decided to take refuge in the relative stability of New York's Chinatown and build new lives for themselves. These actors became Esther's employees, shareholders, and lifelong communal conspirators as she opened her first restaurant, Bo Bo, in 1949.

Located at 20 1/2 Pell Street in the heart of Chinatown, Bo Bo’s was initially created as a respite for all the expat Chinese performers orbiting Manhattan in the early days of the PRC - along with being a natural gathering spot, it assisted Chinese actors with their employment documents and gave them a supportive environment to learn English. This all ended up lending heavily to the restaurant's mystique - most of the commentary I've come across from people who dined at Bo Bo's in the '50s and '60s waxed nostalgic over the beautiful and intimidating actresses who worked at the restaurant more than they did over the lobster roll.

Word of Bo Bo's tight board-only menus and stunning clientele soon spread outside the usual Chinatown network. While New Yorkers have been lining up for restaurants since the dawn of public dining houses, former diners' memories include cramming into the small weatherproof vestibule for the several hours it would take to snag a seat (the restaurant was only twelve tables). That said, according to the quorum on various message boards, the pressed duck, gai kew, sweet and pungent pork, snails in black bean sauce, eggrolls, iron steak, fried shrimp with red sauce, and lemon chicken were all worth the pain. The inestimable critic and bon vivant Craig Claiborne echoed these sentiments when he granted Bo Bo’s a three-star review:

"Legend has it that Esther Eng and her associates, most of whom were of the Chinese theatre, were stranded in New York and opened one of the town's best Chinese restaurants, Bo Bo. [...] The trouble with Bo Bo's is its extreme popularity. It is a small place, notably not elegant, and at times it is next to impossible to obtain a table. However, the fare is worth waiting for."

Esther and her band of partners continued to expand on Bo Bo's success. She opened MongKok (19 Pell St) next door to Bo Bo's shortly thereafter, which is sometimes listed in personal accounts as The Macao Restaurant. Another restaurant, Hing Hing, doesn't seem to have survived in the public consciousness, and Eng's Little Corner (1 Mott Street) surfaced at some point in the mid-50s. But it was the opening of her namesake restaurant, Esther Eng's, that brought real prestige to her dining legacy. Originally located uptown at 58th and 2nd, it joined its sister restaurants at 18 Pell Street in the mid-1950s, where regulars included Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, and Anna Magnani. By all accounts, Esther was still the most magnetic figure to occupy the joint.

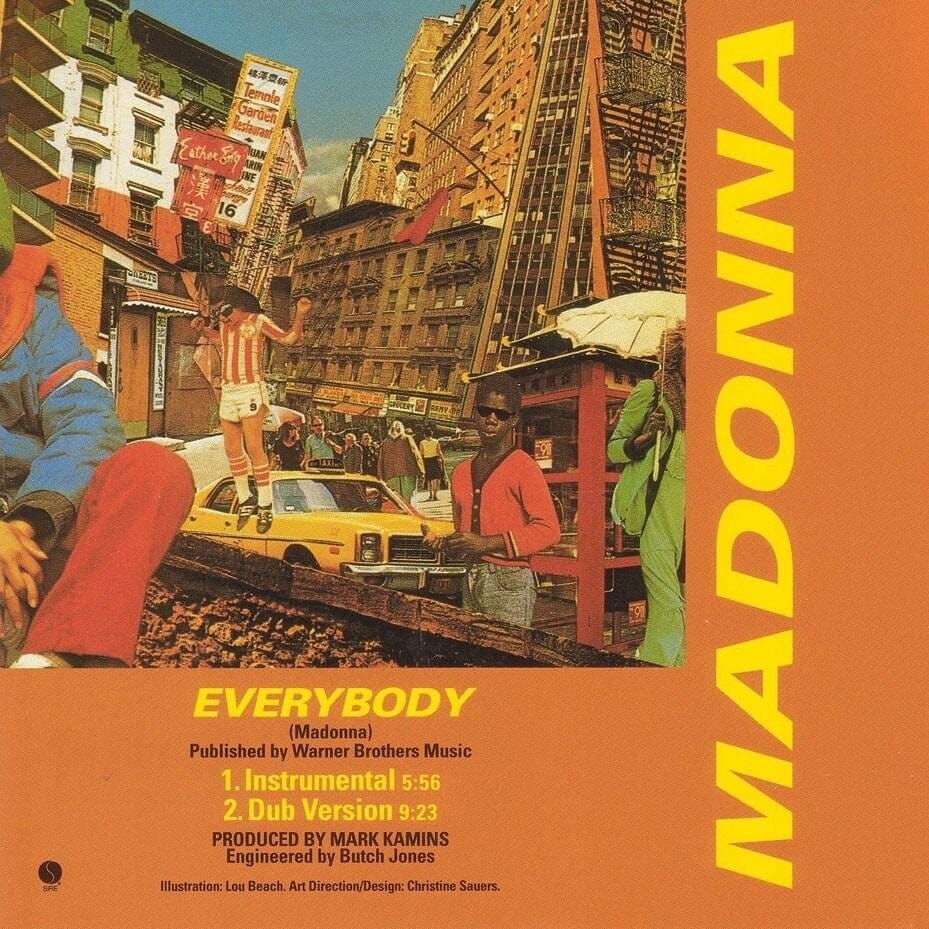

Madonna’s ‘Everybody’ Single (1982) - Esther Eng’s restaurant signage is featured in the upper-left corner.

Bruce Edward Hall recounts his impressions of her empire, notably Esther Eng's Restaurant, in his memoir "Tea that Burns":

"[an uncle]...is now the bartender at the Macao*, one of three restaurants on Pell Street owned by Hong Kong movie people. All three (Bo Bo's and Esther Eng's are the other two) cater to the well-heeled two-martini crowd, but Esther Eng's is the first to eliminate "combination" dinners and American food from her menus. Esther is also unusual because she is an outspoken lesbian, always seen wearing men's suits and "mannish" haircuts. Her ex-girlfriends (of whom there are several) manage her other places uptown."

This is an uncomfortable (and hella dated) spin on it - while the many photos of Esther that survive in Louisa Wei’s salvaged collection do seem to confirm that she was one hell of a Cassanova, it has been confirmed that Fe Fe Lee was at the helm of many of Esther’s restaurants, and seems to have been one of the great loves and confidants of her life. That being said, a chorus of reviews confirms the restaurants were dominated by glamorous, strong women.

It should be noted that amid this restaurant boom, Esther continued to operate her film distribution company, and even owned a 300-500 seat movie theatre (again in partnership with her community of actor/shareholders) called The Central Theatre, which mostly screened Cantonese language films. In 1962, she would direct the exterior shots for what would be her final film, Murder In New York Chinatown, which included some interior shots of Bo Bo’s restaurant.

I think the heart of Esther Eng's New York legacy is best summarized with a tender heart by Hong Kong movie star Margenta Ma near the close of Louisa Wei's Golden Gate Girl documentary:

"She was a very warm-hearted person. [...] She cared about the social well-being of senior performing artists, and new immigrants living in Chinatown. She took care of all of us. [....] If others needed money, she gave them money. [...] If they had no food, she welcomed them to her restaurant. There would be no worries for their three meals. She was really a caring person."

(Apparently, Margenta was the person who also convinced Esther to rein in her gambling habit - although I celebrated her high-rolling hand in the introduction for impact, it appears that she was not a great poker player).

Esther Eng died on this date (January 25) in 1970 of an undisclosed cancer, leaving a crestfallen community and a single English obituary.

I wish there was more of a paper trail regarding her restaurant empire, but I've tried to weave a narrative with the crumbs left for me in memoirs, newspapers, the highlights contained in the excellence that is the Golden Gate Girl documentary, and memories from elder diners who were kind enough to share.

Should any nostalgic diner ever come across this, I'd love to hear about your favorite meal at any of Esther's restaurants, or just your memories of her formidable presence.